David Huang

Interviewed by Rebecca Neely

David Huang was born, raised, trained, and is currently living in the Western Michigan region. He began his metalsmithing education at East Kentwood High School and continued on to earn his BFA with an emphasis in metalsmithing from Grand Valley State University. Working full-time as a self-employed artist since 2003, David is represented by galleries around the US. His work has been featured in Metalsmith Magazine, American Craft, and numerous other books and publications.

Where do you draw your influences from?

I think the core is probably nature; the underlying structures and textures and things I see out in the natural world, but also within my own work. People often ask how I come up with the new designs and all that. It usually is my previous work that is the spur on to move on because when you do a piece, you get to a point where you have to make a decision. Do you go this way or that way? You can only pick one, so I pick one. But then I ask myself “Did it work good there? Or should I try the other?”

That’s something I don't think students get in school so much. At least I didn't. Because you're usually doing a project and then you're jumping to another project and then a whole other project. You don't tend to follow a series in a long line of a half dozen, a dozen, or two dozen related things. Once you actually start doing that, then that past work becomes the influence for the future work. You start to get a deeper design base to work off of.

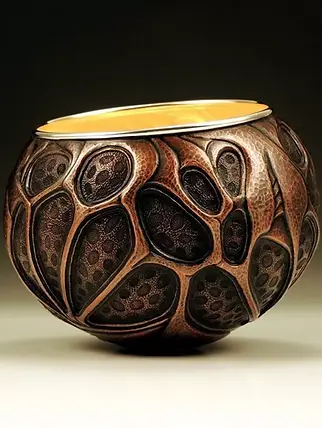

Layered Resplendence 55. One of many collaborations with Edinboro MFA alumni David Barnhill

What led you to become an artist?

I actually began in middle school, 6th grade, but prior to that I was just sort of an average student. In 6th grade I had a great art teacher who thought what I was doing was fabulous. I don't know if she was just making that up or what. But it felt good, so that encouraged me to do more and actually become good at it.

For some reason, at that point I just decided I wanted to be an artist for a living and I never changed my mind. I just kept going with it. It was interesting that as I really got deep into art, which is all about training your perception and learning to focus, because I developed those skills all the other subjects became easy for me. So, I could have gone anywhere I wanted to then, but I decided to stick with art.

Well, I'm glad you stuck with it! So how did you find yourself working with metal?

Following along this line, I was at a school system in high school that was really fortunate. They actually had a jewelry program. It was actually a good art program in general. I decided I wanted to be an artist, so I just kept taking all the art classes I could to the point where I'd taken everything except the jewelry class. And I was like “oh, I don't know. Jewelry... it's for girls. I don't really care about jewelry, but it's an art class. Let me take it.” So, I took it and the first project was sawing metal and when I saw how that hair thin blade, with just hand power, could saw through metal I was hooked right then.

Prior to that, I thought it took big industrial tools to shape metal and when I realized simple hand tools could do it, that was it. I was in. So, then I took all the jewelry classes. I started doing more and more of the jewelry because I knew I wanted to be an artist for a living. I was always doing drawing, paintings, sculpture- everything. But I found in high school my jewelry started selling right away. Other students and art teachers and people wanted to buy it. That motivated me to pursue metals even more.

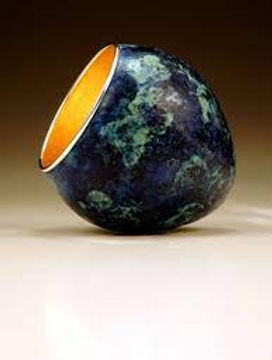

Luminous Relic 1752

Luminous Relic 1658

Why vessels? What is it about the vessel form that draws you in again and again?

Again, this comes back to knowing I wanted to be an artist for a living. I was pursuing a lot of different things and it was late college for me. I ended up taking 12 years to get my Bachelor of Fine Arts, so I never went on to get a masters. After 12 years, what else can I do? But during that time I tried different... I don't know, do I say products? Just different lines, things to sell. Some worked better than others but when I got to the vessels is when everything stumbled together and it became a marketable line of work that people would pay money for. So that's what kept me working into it.

Back into why. I had started with jewelry; I came to the conclusion that jewelry itself wasn't really my passion so much as metal. So, I moved away from jewelry and moved into other things. Initially I think it was larger, more furniture-oriented, sculpture, functional things. I discovered functional work wasn't really that marketable, which sounds odd, but there's a high end of what people will pay for something that's functional because they compare it to something that they can buy that's mass produced in a factory.

We just can't compete with those prices as individual artists.

I found you have to get into the art realm where it's not about function so much anymore, but it's just desire and beauty. And then suddenly there's no high end to it, people will pay more… as bizarre as that is... but that's what happens.

So, as I was moving into other things with metal that weren't jewelry, I learned raising somewhere in college initially and, in fact, I didn't keep my first piece. I didn't finish it well. I said it was finished, but it wasn’t. I was working with a 12’ disc of 14-gauge bronze for my first raising. So, if you've done any raising, you'll understand that's kind of harsh. But I learned the basics of it.

Then when I got into another project, a cabinet for my CD collection, I was incorporating plants in with a bunch of other things but, visually, terracotta pots didn't work. I needed a vessel form and so I raised them out of copper to do that; and in that process I used much thinner gauge and copper, and I realized I really loved the process of raising. It was fascinating to watch it develop from a flat sheet into a vessel form. So that's what got me started with that and I just kept pursuing it.

It was a while before I brought the chasing work into it. I did chasing already; I'd sort of mastered it when I was doing jewelry, but I never brought it to the vessels because I was using pitch originally and I just do not want to fill the vessel with pitch or even empty pitch out of a vessel. But when I stumbled on using wax instead of pitch, which is so much easier, that's when I brought the chasing into it. Chasing is what allowed me to really move the vessels artistically, beyond just simple forms. I could really get into complexity, so it now has this long breadth of things to explore artistically, where I haven't gotten bored with it.

My early raising...it was all about the form and I was fascinated by how the personality of a piece changed just by how slightly you change the curve. It was interesting to watch how different people would respond to the pieces just based on these subtleties. Certain ones grab them and other ones don't.

I’ve noticed that- especially with smaller objects that you can hold in your hand- people love to touch it. With chasing and repousse, they just want to feel it and experience it. I think that's what kind of brings a little bit of magic to the work.

An interesting point, veering off to how people interact with the vessels, I do find that too. Most of my normal size are hand size and people want to hold it and look in their hand and, you know, feel it and all that. I've done some big ones as well and I found that once you get to a certain scale, the way we respond to it physically changes. People stop wanting to hold it and peer in. The response I seem to get with the larger ones is they want to crawl into it, even though you physically can't, but that's how people change their reaction to it. I find that fascinating.

What size do you usually find that with? I've seen a picture of you where you're working on a vessel that looks like it's the size of a person. Is that the size you’re talking about or is it smaller than that?

I found I often think of vessels in terms of the size disc I started with. So, the one you're talking about in the picture, I'm pretty sure is the one that I did from a 4’ disc. That is about the largest a single person can reasonably handle. Well, at least I don't think I can go bigger, but I find for me it's when I start from about a 2’ disc; that's where the response seems to change. The 2’ disc ends up with the piece roughly 1’x1’ as the final dimension. That's sort of where people start to respond like “I want to crawl in.”

David Huang chases details into a large vessel, which began as a 4' disc of sheet metal.

What is your favorite process?

I don't know. In general, favorite doesn't mean a lot to me. Right now I probably enjoy the chasing more because it has more artistic exploration for me. But that's not to say every day I do it. There are some days where I don't want to think as much and raising, for me, is like this mindless activity. I can just go and raise. Or patina day; that can be exciting as well. At this point, where I'm at, most of the processes I get kind of bored with at certain stages, but chasing is the one that's keeping me most involved, I think.

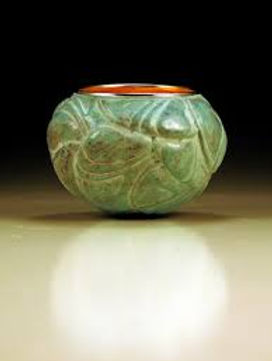

Sensual Radiance 1838

Luminous Relic 1813

Do you begin with a plan or work more intuitively on each piece?

Yeah, in general it's more intuitive. When I start, I make my decision- “Is this going to be a multi node vessel, working off of three points? Is it going to be a pointed vessel, really bringing it down tight? Or is it going to be shallow or circular?” Like, I have a sense of the general form. But that's about it at that stage. I usually raise up a bunch at once and then later I'll decide which ones I pull off to use for planishing or not for planishing, for chasing later, and which do I just leave as the simple forms for more of my luminosity series.

Then, when we get into chasing, I used to always draw them all out completely before I started. I still do that sometimes, but lately I'll design a layer and then usually it's kind of broad. I want each layer to work on its own. But then I'll chase that in and then I'll look at it and say “OK, now what would the next layer of design be like? How can I make this more complex or more interesting?” and go from there. So, I don't always have an end goal in mind exactly.

Luminous Relic 1575

You usually work in batches, right? How many pieces are usually in a batch?

So, generally, when I do the raising, I'm working on 6 at once. But then I will raise up a bunch of those and I'll usually have a box of the raised ones. And then, when I just don't want to think, I'll pull them out and start planishing them. When I'm doing the chasing work I usually have at least 2 going at once. I do the chasing on one, then I melt the wax out, anneal it and let it pickle, fill it up again and let the wax cool. While that wax is cooling, I have the second one I can start working on. In the overall batches… usually it's somewhere between 12 to 24 is what I have going before I get to the finished stage where I make the silver rims out of them and do all the patina work, then do all the gold leafing. So, the actual batch tends to be about one to two dozen.

Lucent Terrain 1844

How long would you say it takes for each piece to be finished?

That definitely depends on the piece. What I call the simple form ones, like the humanity pieces where it's the raised vessel, it's about the patina; it's got the rim, the gold leaf, but doesn't have all the chasing work in my normal scale. I'm working from a 6-7” or 8” disc. Roughly speaking, start to finish, if I condense the time because again, I'm working in batches so I never quite know… Figure those take me about a day to do. Maybe 8 hours?

I'm pretty fast at raising. Once I was like “how fast could I do it?”; I think I was working on 9 vessels at once, hammering them out and trying to keep time to get them all from flat to the basic raised form, not including planishing which is the slowest stage. It worked out to about an hour and a quarter for each one. Which boggled my mind. And then it's usually another half hour, 45 minutes to planish.

But yeah, that's the batch work. I probably had it split in half or something like that; I'm raising four or five of them and then I run and anneal them all as a batch, put them all in the pickle, and then I'm raising the others so they're ready to come out of the pickle when I'm putting these in.

So that way you can keep moving?

Yeah, the efficiency is in doing that. When I'm doing the chasing work, that's really where the time gets involved. So, again, a smaller scale vessel or when I think of my normal scale, chased out start to finish, is usually about a week's worth of work. And that can depend on the complexity. A 6” vessel or an 8” vessel... there's a big difference in chasing surface to do there, and I seem to be getting more and more involved in my chasing, so I'm not even sure that that figure is accurate anymore. I'm probably beyond that, doing week and a half or two weeks now.

So, you’re a fast worker and you've been doing this for a long time. Your pieces all have a number in their name, such as Luminous Relic 1152. Does that number signify how many you've made thus far?

For the most part. I figured there were about 1000 before I started the numbering system. I hate titles and I realized I'm going to be making a bunch of these... like, there is no way I'm going to try and come up with a new title for every piece. So, I developed titles for the major groups or bodies of work.

Then I decided, just as a business thing, I have to have a way to keep track of each individual piece so that I know what gallery it went to, who bought it, all the material costs that are involved in each one, and what the number is.

I have two numbered series. There's my solo work, like the luminosity, radiance, the luminous relics. Those all have numbers behind them, but they're all in the same sequence. So, looking at my file cabinet here, this is the last one I finished. It's suspended radiance #1867, so that's number 1867 I've done in that series.

Then there's a second series that I’ve been working on with David Barnhill; the layered resplendence where he’s doing mokume-gane. So, with him, I decided I did need to do our own non numbered series. We're up to #71 on that, which is actually kind of surprising. We've made that many pieces. That's what the numbering system is. It's not a glamorous thing for a title, but it's something. It works.

Are you driven by the process? Or the final goal?

It's a bit of both. I think I am mostly a process person. I tend to like routines in general, so there's the comfort of the routine. My usual work routine when I'm really into producing work is… In the morning I'll go out and I'll raise for a couple hours out in the studio, and then I'll come back inside and maybe make lunch or whatever, and then spend the rest of the day into the evening just sitting down and chasing. I'm soothed by that process. But then when I'm doing that for too long, I start to get a little bored with it too, and I don't feel like I'm getting anywhere.

That's where I often find I always need to do smaller batches because there's this great satisfaction that comes when I'm actually bringing them all together and to the finest finished piece. It's like, “Oh, hey, this really is a nice piece” and I enjoy that, there's a bit of volume on that.

A confidence boost every now and then.

Right, exactly. It confirms I'm doing something good here. I'm making real things.

Luminous Relic 1852

Did the pandemic affect your practice at all?

Yeah, I've been working towards early retirement, and this is where things did just kind of slow down, especially with my galleries sales; just all but dried up and stopped. Not completely, but mostly. And I was like, “OK, do I panic about this or what?” I just decided, “well, you know what, this is kind of a good time to try semi-retirement” trying to mentally put myself in a space where I don't need to worry about it. I can look at my financial numbers and I know I don't need to worry about it, but I still get that stress because money isn't coming in. In fact, I was just thinking about doing my end of month figures; I don't know if I sold anything this month. So that's where I decided with the pandemic that it's a good time to just ease off and cut back.

But I guess the other interesting thing that happened during the pandemic was the idea of making jigsaw puzzles with artwork on it. You may have seen them on my website. I did a couple of my own work and one with the collaborate piece of David Barnhill. I also wanted to explore other artists I know whose work would make great jigsaw puzzles. So, I produced these four different puzzles, which the timing actually worked out perfect for the pandemic; everyone was staying at home and jigsaw puzzles were big.

That was kind of cool, but as a part of that, I realized I needed to change my website because before, when people wanted to buy things off my website, they had to e-mail me and ask, “is this still available?” so then there's that e-mail exchange back and forth. I'd never really set up a click and buy sort of e-commerce thing on the website. Frankly, I didn't think anybody was going to just click on and buy a $1000 piece off a website. That seemed insane to me even though I know what happens elsewhere, but I just didn't visualize that happening. But for these jigsaw puzzles. I realized I had to do this because the margin of where I make money on them is really low, so I can't be spending half an hour to an hour just emailing people to get this thing put together, and pretty much have to have it where they can click, I get all the shipping information and money is all handled.

I did that for the puzzles and thought “OK, I'm already set up. Let me put in the vessels and the other artwork” and I was surprised that the vessels started selling. So, even though my sales through galleries during the pandemic took a nosedive, I saw a big increase in sales directly off of my website. That actually worked out really good and I’m kicking myself because I should have done that a decade ago.

Layered Resplendence 62, in collaboration with David Barnhill

Luminosity 1827

Have you ever experienced burnout? And if so, how do you push through it?

Yeah, that happens periodically. It's a cyclical thing, but not a regular cycle. Early on, as I'm doing this for a living, there's the flat out financial motivation of “I got to make work, I got to pay the bills.” It's just that I may not want to. And like, OK, maybe I'll take a day or two off and just don't work. That's the nice thing about being self-employed, that I can do that.

What pushed behind me though is that if I'm not getting work done, then I'm not getting paid. I've got to get the work done and then it's still going to be months before I get paid for that piece. Usually you know that it's fine; you know the client who wants to buy it and all that. That's always kind of been the underlying motivation to get over the burnout or work through it.

Lately, that's not quite the same motivation. I've been playing at being semi-retired. I don't need that much income anymore; I still have to work a little bit, but not much. The financial push to make me work is not there anymore. So, I'm not working as hard, especially when I'm just not feeling motivated. Something I've been trying now is to branch out into other directions. What if I don't need to make work for money? What kind of work do I want to make? I can do things that aren't as marketable. Or I can pursue things that aren't necessarily art. What do I want to do?

Again, I think I'll take longer breaks when I'm not working, but it still ends up coming back to, once I get back working, like “oh, I'm just comforted by this routine” and so I get back into it. With burnout, a lot of times I just have to start really focusing on a piece and to really look at it and not just be going through the motions. But to really look at it in the design and then I can start to fall in love with the lines and the textures and the patterns, just all the undulations and curves. I've got to focus my attention again.

A table puzzle based off David's work, Luminous Relic 1752, available on his website.

Do you have any advice for art students who are about to graduate?

What I observed over the years was that most students weren't prepared in this way. So they graduated, needed money like we generally all do, and thus shifted to working whatever readily available jobs were in front of them at the time. Usually this meant working more at wherever they were already working. Generally, the plan was that they'd work to earn money and eventually buy the equipment they needed for whatever their chosen media/technique required. The key word here is "eventually".

In reality, the day-to-day routines, challenges, and grind of life meant that eventually went from weeks to months to years. At some point they ceased thinking of themselves as artists. Art was just something they once did and might do again after retiring from whatever job it was that took over their life. This doesn't have to be a bad thing. Most people have very strange routes to whatever eventually becomes their major life careers, winding up doing things they never would have imagined. If the result is a fulfilled life of purpose, then all is good! However, if you really want to be an artist, what I've observed is that you need to have the physical space and working routines set up in place so you can continue the practice unbroken in time after graduation.

I'd highly recommend the book "Your Money or Your Life" by Vicki Robin. Mastering finances, regardless of how much or how little income you have, is a huge thing so often overlooked in art programs, and general education overall. If you follow the suggestions in that book, you'll gain a far better understanding of yourself, what brings you fulfillment and what doesn't, and how to devote your life energies and money to things that do. As an artist this means how to sculpt a satisfying life focused on making art as your primary activity rather than getting waylaid in the pursuit of money (always seeming to need ever more of it) while your art becomes a future dream and occasional pastime.

As we talked about, I also spent 12 years getting my BFA and over that period of time I watched many hopeful art students graduate and move on to their next phase of life. Sadly, for far too many, their senior show was actually the culmination of their "art career" rather than just the start of it. From what I could see, a big reason for this was that they weren't prepared with a physical space to actually make their art in. They had been relying on the tools, space, and equipment of the university to work in. These facilities are fabulous to learn with, allowing one to explore a range of media and techniques to see what ones ultimately resonate most with you and what you wish to express through your art. However, unless you have unlimited funds to establish your studio with, you need to settle on a limited number of media or techniques and acquire at least the minimum amount of tools/space to work in once you graduate. You want to have your studio set up and equipped BEFORE you graduate!! Ideally you will have also established some sort of working routine in this space too, such that you are doing most of your work there rather than at school by the time you are ready to graduate.

Chasing progress during the making of Luminous Relic 1752

Lustrous Contours 1865

What led you to begin making your own tools? How did you learn those skills?

The short answer is poverty! For many years I made very little money and hadn't learned financial management to any serious degree. I flat out couldn't afford to purchase many tools, so if I could make something that is what I would do.

Later, the making of tools became a thing for doing the workshops I began teaching. It's challenging to find venues with enough raising stakes to run a class of 12 students all hammering at the same time. The same holds true for chasing workshops. At one point I did have people making the majority of the tools I needed to run these classes, but two main issues lead me to start making them myself.

First, it seemed no matter how much in advance I'd order the tools they were always finished just barely in time for the workshops. Granted they were always done in time, but I knew if anything went wrong, I'd be stuck with a class to teach and no tools to do so. I could pass off blame on those who were to make the tools, but really it is my responsibility to make sure I had them for the class. Ultimately that has meant making them myself.

The second main issue is financial matters, the recurring theme in so many of my answers. When I had others making the tools for me it was not uncommon for me to have $4,000 to $8,000 invested in a workshop before the class even happened, or I saw any income from it. Again, this is why learning to manage finances has been so important to my success as an artist. I was able to front this kind of money to make the workshops happen, but it was nerve-wracking when the tools were always getting finished at the last minute, running the risk that the workshop would be a complete disaster, financially and otherwise, if the tools didn't show up! By taking on the task of making the tools myself I can make sure they are done well in advance. As a major added bonus, I also get the additional profit from their manufacture and sale. The serious downside though is that making tools is not nearly as much fun as making art.

As for how I learned the skills, as I like to tell my students when I show them how to make their own chasing tools, "We are metalsmiths, who else is going to make these?" What I do is basically just grinding and shaping metal like we might do making jewelry, only on a slightly larger scale. I learned the basics of hardening steel from Tim McCreight's "The Complete Metalsmith" book, which likely most reading this already own. I suppose I did learn more of these skills from my time working as a metalsmith for a sculptor who did larger scale work, along with my time at a small business that make hand tools for the sewage and septic industry. I did a lot of basic cutting, welding, grinding, and finishing work at those jobs.

Based on your website and Instagram posts, it seems like you've made efforts to create a more eco-friendly homestead. Have you taken similar steps in your studio practice? What tips or advice do you have for artists who are interested in doing the same?

Progress shot of David standing upon the tire walls of what would become his studio.

David Huang's studio

I do have to acknowledge that as a metalsmith I am using a material that involves tons of embodied energy and environmental damage in the extractive mining, smelting, and refining of the ore bodies into the pure metals. I feel like it's my responsibility to try and use this resource to make things that will be valued and last for generations.

My suspicion is that one of the lasting legacies of the fossil fuel era we will leave for future generations will be the vast abundance of refined metals. In that vein it would be nice if we could also leave them a living skill set to be able to keep reusing and reworking this material once the cheap abundance of energy those fossil fuels provide are gone. Thus, another reason why I like simpler hand tools; less complex tools require less to build and maintain. It's more likely they can be repaired when things break, rather than becoming scrap. Thus, my tip for other artists who are looking to make their studio practice more eco-friendly would be to think seriously about building your practice around hand tools, things you can make, adapt, and repair yourself. Try to consider everything through the lens of energy use. How much energy is required to make things and operate things. How much energy is embodied in the materials. Is this energy going into a short life cycle or a long enduring life cycle?

All that said, I think we do have to acknowledge the era we are living in. Tradeoffs may need to be made to be economically viable within our cultural systems. For example, electronics have huge embodied energy footprints and short life cycles with lots of hard to recycle waste streams, yet having a viable art career without utilizing the internet, and all the tech gadgets involved, would be a huge feat I think. I just try to minimize what I can and do the best I can. In general, if you can live with less stuff, you will be reducing your negative impacts on the ecosystem. It's also worth considering things one can do to actively build healthier, resilient, biodiverse ecosystems. The living roof of my studio might be a small example of this. It's a habitat for all sorts of plants and insects while being a roof layer that uses the sun's UV light to rebuild itself every year creating more topsoil and biomatter instead of slowly degrading asphalt shingles or whatever else we tend to use at the top layer of our roofs.

I have indeed put a lot of effort into building a more eco-friendly homestead. I was always interested in this, but early on, when I was quite poor, thought I couldn't do much in this regard. The good news is that, as a general rule, it turns out the most eco-friendly things we can do are also the cheapest!

For example, about 10 years ago I took my whole homestead off the electric grid, making all my own power via photovoltaic solar panels with a battery bank. One could consider this an eco thing. It was also an expensive eco thing.

However, the best thing I did for the environment was actually in the years before I went off grid where I worked hard to develop and adapt my life to systems that used far less electricity so that the solar array I installed could be much smaller. Learning to use less power is way cheaper and better for our environment than using power generated from solar panels. In a similar vein, having a small house and/or studio is way cheaper to build and maintain than a large one. That reduction in resources needed is also a reduction in resources we are extracting from the ecosystem, and waste we are generating.

I suppose one could say I've taken similar steps in my studio practice. The first thing is that my studio is on my homestead so I'm saving myself and the planet all the resources I'd otherwise expend commuting to and from it daily. My official metals studio is an earth sheltered building I built using the "earth ship" technique of rammed earth tires. It was actually the first part of my homestead to be off grid, utilizing solar panels to generate all the electric power. Though I have to say I really don't use much electric power in the creation of my work. Mostly it powers the lights (focused task lighting for the most part), radio, and exhaust system (only used when needed). Much of my work is done with hand tools powered by my muscles, in my case, hammers and chasing tools.

I did shift several years ago to doing my chasing work inside the house proper rather than out in my studio. The reason being that I had switched to heating my home primarily with wood which meant I needed to be around to feed the fire. It just seemed silly to run back and forth between the studio and house, working to keep both heated, when I could just set up a station for doing the chasing work inside. I find I don't need to heat the studio in the winter when I'm out there doing my raising work. A few layers of clothing and the vigor of the work keeps me comfortable enough. The earth sheltering of the building keeps it from getting too cold all on its own.